In our upcoming podcast we explore the theme of art, performance and forced migration, speaking to a number of artists and writers who have first-hand experience of displacement. We will discuss the ways in which they use their art and writing to understand and move beyond their experiences, but first, let us introduce the artists and showcase some of their powerful and beautiful work.

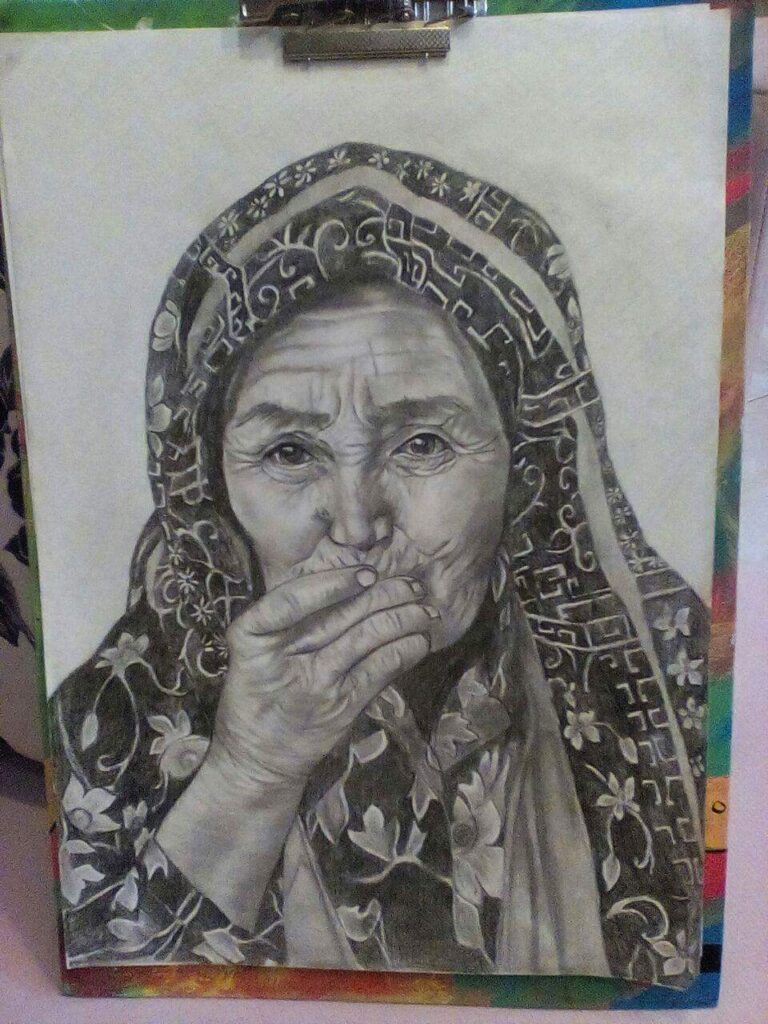

Parmis Vard

Parmis is an Iranian artist based in Austria. She fled her home in Tehran for political reasons in 2015 and made the journey to Europe. It was a stressful and turbulent time, but as she told us: ‘I’m OK now, I am safe’. Parmis collaborates with the refugee art enterprise, RESTART, and her work has appeared in numerous exhibitions connected with migration and women. Her work focuses largely on portraiture using pastel.

Below, you can listen to Parmis talking about her work.

“Once I saw a photo that reminded me of myself, so I just thought I would paint a face like my own, and for me blue is the colour of peace and calm. Darker blue shows inner turmoil; my dreams, my soul are blue. And [in this piece] I just want to say to another person ‘just give me peace instead’. I think this painting represents me and all of the people who are looking for peace, and with this painting I wanted to tell the world ‘listen to the silence of the human: don’t become this colour blue that is darkness.”

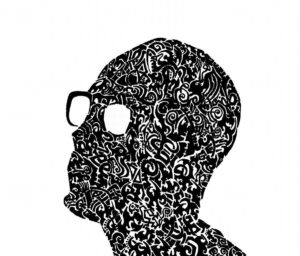

Manaf Attar

Manaf Attar is a Syrian Artist who left Damascus in search of a place where he would not be forced to fight other Syrians, and where he could be himself. He is currently based in Berlin and works with the German contingent of RESTART. Although he does not call himself an artist, his work continues to evolve from the small black and white patterns and doodles he makes in his notepads to large scale drawings. His work has been displayed at exhibitions on migration as well at music festivals across Germany.

Below, Manaf discusses the process that goes into the creation of his pieces.

“So the thing is that my work is starting to change again because I had some kind of a plan that I would cut off trying to make any kind of ‘art’, but just focus on this thing that I am doing now, and really keep doing it until it becomes like a technique that I’m able to do almost blindfolded. It’s just like as I see it. For me, my favourite colours are black and white. I prefer anything that is black and white, even in pictures I like it way much better. So I just kind of have the same patterns, the same kind of drawing, but it’s always changing because I’m putting it into different outlines.

That’s why I am telling you that I am not seeing myself so much as an artist especially in Berlin because artists here are all in all, they can do everything, you know you can give him a sprayer and he gives you a graffiti that’s three metres, two metres big. So now I’ve reached the level again where I’m really good with this black and white stuff and I want to start adding colours and some digital art.”

Yousif Qasmiyeh

Yousif Qasmiyeh is a poet, translator and tutor of Arabic at the University of Oxford. He was born in the Baddawi camp in Lebanon and its influence has shaped his literary work. He is currently the Writer in Residence for the Refugee Hosts project , which is designed to find creative ways to foster dialogue within refugee camps between refugee host communities and incoming refugees. The project aim to use literature as a way of investigating how cultures change inside refugee camps.

Yousif has explained what is behind a recent poem, ‘If this is my face, so be it’: “The main idea I would say is how the face of the refugee is an entity on its own, and how the face is there to remind us that movement has a face, that departure has a face, that not being able to survive also has a face. I think that writing from the premise that people are dying is important. People are not just dying while being static but while on route and moving, and this is something that ought to be focused on. It is as if there is a choice here simply to die on your own, without moving, or to die while resisting and trying to be able to see what’s beyond your own place in order to survive.’

You can listen to Yousif read his poem below:

If this is my face, so be it

Walking alongside his shadow, he suddenly realised that it was both of them who needed to cross the border.

They fortified their walls with cement and nails. They moved their women and children to a safe place and shouted: they are coming after our faces; they are coming after our crops!

Immemorial is the smell of refugees.

Wake! He said to his body when they arrived. A bit of air was in the air.

The equivalence of a refugee would be his body. Whoever can sense the coming is a refugee.

The refugee can neither come nor depart; he is the God of gestures.

We might also say the face is a dead God.

Whoever claims asylum, whoever lends his hands to strangers so they could bear out his presence and his things is the one who has many deities and none.

Refugees to kill time, count their dead.

Killing time is the correlative to killing themselves.

Look out for our upcoming blog and podcast in which we focus on refugee artists and performers and discuss the relationship between art and forced migration. Please sign up to our newsletter at the bottom of this page for all the MOAS news and updates and support our rescue missions by giving whatever you can to help us save lives at sea.