Welcome back to MOAS… In this episode we’re looking at Refugee Art and Forced Migration. We’re going to speak to organisations and artists using art in different ways to learn how host communities and refugees can talk to each other and to make new lives in Europe.

Stay tuned to the end as we’ll be talking to the creator of a campaign telling us not to forget the contributions of refugees. It’s a rant inspired by American hot sauce that goes into relativity, music and activism.

Let’s start of by looking at Refugee Hosts, an research project exploring the relationship and experiences between refugees and host communities. Their research focuses on nine specific communities in Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey, together hosting over five million refugees of the Syrian conflict. It’s hoped that by setting up creative writing workshops the hosts and refugee communities can understand what hosting means and breakdown the negative stereotypes of refugees.

Elena Fiddian Qasmiyeh is the Project Investigator…

So what we’re really looking at, which has been under-explored in the academic research and also in policy and practitioner literatures, is the extent to which refugees become hosts to newly-displaced groups, in this case from Syria. So there are commonalities across Jordan and Lebanon insofar as large numbers of people displaced from Syria have found safety or at least spaces of protection to a certain degree in the Palestinian refugee camps themselves. This really highlights the need to have a historical understanding of the processes of displacement. Baddawi refugee camp in Lebanon, for example, where we’ve been conducting research, has been home to around 40,000 Palestinian refugees since the 1950s, but also in the 1970s became home to refugees from the Tel al-Zaatar refugee camp in North Beirut, which involved a large number of people being displaced at that stage in 1976. Then in 2007 again, Palestinian refugees from Nahr al-Bared within Lebanon were also displaced when that camp was destroyed.

So Baddawi refugee camp has been home to different groups of Palestinians displaced within Lebanon – it’s been hosting different generations of refuges in that regard – but has also now become home to refugees from Syria, including Syrians but also Iraqis and Palestinians who had previously been living in Syria. So these spaces are very complicated spaces with many different social dynamics, but they’re places not just of refuge but also of hosting. So refugees arrive and then they become host to new communities, and that’s one of the key issues that we’re exploring to actually identify: how a community can become a sustainable community of welcome, a community that can endure the reality of being in a very precarious space and also offer safety and protection to different people at different stages.

So you want to look at how hosts and refugees interact in context, but why use creative writing workshops?

My colleague, Professor Lyndsey Stonebridge from the University of East Anglia, is one of the co-investigators on the project with myself and two other colleagues. She’s a professor of Modern History and of Literature and she’ll be running the creative writing workshops with our project writer-in-residence Yousif M Qasmiyeh with the support of our project partners, Pen International and also Stories in Transit.

So, the backdrop to running these creative writing workshops is that we know that refugees are often framed in the media and in NGO reports as suffering victims, and refugees’ experiences have often been silenced because people affected by conflict are expected to fit what we can call a humanitarian narrative. And this narrative runs along the lines that refugees are passive victims that need international assistance, rather than recognising that refugees have always found solutions to their own problems, and those of other refugees, and indeed that refugees are active agents who have creative ways of responding to their experiences of displacement, not only to stay alive, but also to live meaningful lives.

So, what we’re aiming to do to challenge a number of assumptions relating to “the silent suffering victim who is awaiting an international saviour to come in and offer them protection”. Rather, we’ll use creative writing workshops to offer a creative space for participants to simultaneously document, trace and resist experiences of, and also responses to displacement. So the participants involved in the creative writing workshops, which will involve both refugees and hosts, will be invited to reflect on their own journeys and their personal encounters, including their journeys in and out of displacement and in and out of hosting experiences as well, so experiences of having hosted other people in the past, and hosts’ experiences of having been displaced in the past.

So rather than thinking about writing through experiences of displacement, one of the key aims of the creative writing workshops is to think around “what does it mean to host and be hosted, and how does one critically and creatively write about these experiences”. And then together as groups, we will be exploring how refugees and hosts’ stories connect in time and style and motif, and the stories of other people, from the present and from the past. Then we will be presenting these stories to connected audiences in the Middle East and in the UK. We’re aiming to challenge the image of the individual suffering refugee by providing evidence of the creative resistance and the traditions of the refugees and hosts alike. We’re aiming to create communities of story-telling and communities of creative resistance through creative writing workshops.

Let’s find out more about why literature helps Refugee Hosts from its Writer in Residence. Yousif M Qasmiyeh is a Palestinian poet, translator and Arabic tutor at Oxford University. He was born and brought up in Baddawi refugee camp in Northern Lebanon. Using his own experiences, he’s helping Refugee Hosts examine how new people and languages entering the camps are evolving.

When Refugee Hosts started we also thought of employing literature to give ourselves the opportunity to transcend mainly the ‘social science’ mode of thinking, and to see what literature might bring us and might maybe provoke or invoke in these surroundings and these settings. That’s why I’m part of it, and I am also a refugee. I am trying to see things the way for example I would see them as someone who is there. Although of course I no longer live in Baddawi, I live here in Oxford and I teach here, but I am trying mainly to say to myself that bearing witness has nothing to do with ownership, bearing witness has to do with observing and to observe with a degree of subtlety and sensitivity. I think that through these sensitivities we are trying to see how people are interacting with one another and how literature and the concept of the narrative is evolving, and these are main things that have attracted me to the refugee hosts and to say to ourselves: but who is the host, in fact, and who is the refugee?

I think that these questions are very pertinent these days because it is so important to disrupt this humanitarian hierarchy and to say at times that giving has to do with taking away. It’s not just a benign act; there are clashes, there are collisions, there are things that are happening that maybe are being concealed and things that we’re are trying to investigate, to investigate, using of course, in addition to social sciences we are using literary lenses.

You are ‘writing the camp’, what do you mean by this?

When we thought about writing the camp we thought of simply investigating the verb itself, ‚to write’ and to write as an archaeological act but also as a literary act that is happening, and not just happening from our own perspective but also happening when we are not there as well. So this ‘happening’, or this let’s say continuity, is not just being observed when we are there. We know that people are also responding to these states maybe by let’s say taking photos of things. Now as you know there are smart phones, so you can see how refugees are taking photos of themselves in camps and saying to their friends – let’s say Syrians who are based maybe in Europe – “now I am part of this community” and I think that trying to use photography and also to use certain sites such as cemeteries, where people die and are buried, as places that are inviting a change.

Before, we used to take these things for granted, but I think that the arrival of these refugees and the way the space itself has become congested, maybe I don’t know how to state such a thing other than referring to dying. Before, the dead used to be sent back to Syria, but now they are accepting being buried in the camps. I think that this is a fascinating and a sad shift at the same time because people are stating their background on the tombstone, and I think that when we see the word archived we see how this piece of marble is inviting us to simply speak to this solidity and to say that these people wanted first to assert their presence as people who are buried there, but equally also refer us to maybe origins.

I think this dichotomy is somewhat not just intriguing and interesting but it as if it has continued this question of solidarity beyond life and living to the space of death and dying, and I think that’s why we do not know how to assess our progress or assess what we have achieved, but what we can say quite vigorously is that at least we are managing to capture some of these changes and some of the elements that are happened. And not just happening and being monopolised by certain groups but often times shared.

Now, let’s return to Central Europe and find out about a project called RESTART. The social enterprise was created by German business student Jonas Nipkow. Inspired by working with artists from conflict zones, Jonas wants to give newcomer artists coming to Europe a way to produce artwork and make money. It’s been running for a year and RESTART now supports almost forty artists in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands.

So, the original thought of RESTART was first to build up an online marketplace for art made my newcomers so they could present and actually sell their artwork and get some additional income. We haven’t done this yet for several reasons because actually before selling art you actually need is tools and studios and so this is where we’re kind of focused on. When we had our first exhibition in April 2016 it was just planned actually to make people aware of RESTART and what we planned to do the with online marketplace but what we realized is during this exhibition that this is the opportunity where people actually meet and get to know each other and there’s always so much talk about newcomers online and even those who have the refugee welcome attitude don’t actually know a newcomer in person which kind of motivated us to keep doing these exhibitions and see this as a great opportunity to bring locals and newcomers together.

So we had a couple of exhibitions here in Berlin and we participated in big music festivals in Germany, there was two or three coming up this summer where we have outdoor open-air exhibitions with two or three artists then we have a couple of local groups in different cities so what they do is these are people reaching out to artists in their community and we help them organise exhibitions in Gera city, so it happened in Hamburg for example or in Vienna, close to Amsterdam. There are many different opportunities, institutions approaching us ‘hey would you like to exhibit something’ and so there’s always an opportunity that we can offer to the artists to present themselves and participate in the exhibition.

How did you connect with the refugee artists you support?

This trip to Israel and Palestine and the thoughts I had afterwards I shared with my personal network on social media. I told people about what happened and that I would like to start something like an online marketplace and support newcomer artists who recently arrived to Germany and Europe. Then people started commenting on my Facebook post and linked me to other people that are engaged with the work of newcomers and then of course once you meet one artist you find another artist, and interestingly most artists that we work with come from Syria and when they come from Syria and have an art background, most of them studied in Damascus because as far as I understand and I know there’s only one opportunity for people to study Fine Art in Syria and that is in Damascus. So maybe particular artists are based in different regions and different countries and if I meet them I suddenly find out that they know other artists that we work with for the fact we’re based out of the same university.

What does their artwork express?

It differs from artist to artist, but what I can say is the experience they’ve made through the past couple of years with the war situation in Syria it’s something that you pick up most of the artworks. There’s a lot of pain usually, one can see it in the colours but what I would also say is that many artists also include some colourful notion into their artwork symbolizing hope and peace. So, on the other hand there are also other artists completely try to avoid the topic and just find and also an opportunity to maybe keep themselves busy with something else than the conflict or situation in Syria when doing art and this is why they don’t discuss it in their artwork. But I would say yes for most of them that that actually applies actually use art as a tool to express themselves and use it kind of therapy for themselves.

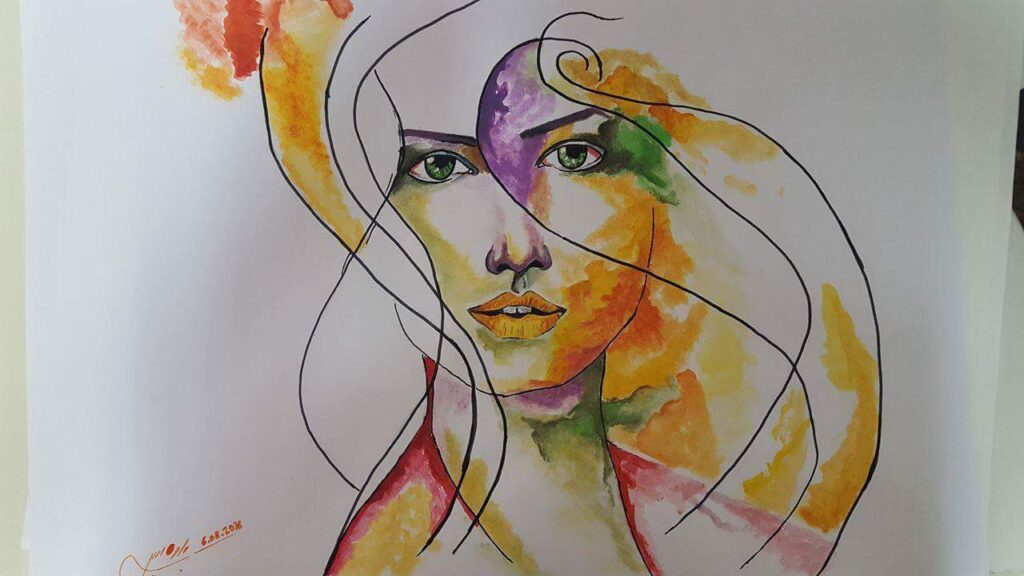

Parmis Vard is an Iranian artist who fled her country because of political turmoil. She’s currently in Austria and has been exhibiting her work at numerous events with RESTART. Created with pastels, her portraits of people are a shock of colour reflecting turmoil and the pursuit of inner peace.

My art it gives me strength to fight the difficulties and it helped me to get out of my innocence, and it forces me to have a goal in the world and my goal is to remind that we live in a strange and peaceful world.

Is there a message you try to share with people who view your work?

Yes, I believe that every human has feelings within themselves that come out and are novel to others. I believe art is inside everyone and you just need to be expressive. We focus our dreams and our souls and just looking for physical relaxation and for that we forget each other and ourselves. And I just have a question in my paint, what are we looking for, what is our dream, how much do we pay attention to ourselves and that is the question in my paintings.

Can you tell me more about what inspired your painting, ‚Blue‚?

Once I saw a photo that was in this form and it reminded me of myself, so I just thought I would paint a face like my own. For me, blue is the colour of peace and calm and I believe it’s been the blue if darker it shows inner turmoil and my dreams, my soul is blue. And I just want to say to another person ‘just give me peace instead’ and I paint the board blue and I think this painting is me and all of the people who are looking for peace and with this painting I wanted to tell the world ‘listen to the silence of the human and don’t become this colour blue that is darkness’.

Do you have a plan for the future?

I want to study architecture and continue my art too. I hope that RESTART can support more refugee artists and we can together keep alive art and give peace to the whole world and show the world that we don’t give up. And painting for exhibitions my work helped me find meaning and purpose in my life as new artist in a new country and I hope the rest of the artists will find their way too and find themselves. I also give painting lessons to young children in the refugee camps, most of them are from Afghanistan and Syria. I hope that in the future we can teach painting to children in many other countries. So yes this is my hope for the future.

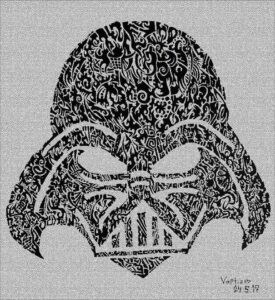

Manaf Attar is also a newcomer artist working with RESTART. He fled his home in Damascus, Syria to avoid being conscripted to fight other Syrians.Since moving to Berlin and working with RESTART he’s presented his evolving artwork at exhibitions and music festivals. Art is an important therapy for him.

…I really stopped any kind of drawing, any kind of free hand stuff with the pencil or whatever I just focused on this one thing that I’m doing because it’s nice, its making me feel good, it’s becoming like a meditation. Whenever I’m not feeling that nice or I just want to loop out from people I just hold the pen, don’t even think what I’m going to draw, it’s just like I’m writing or something, I don’t even look at what I’m drawing really. And I’m just listening to some kind of music or whatever its always like a meditation to me, it really became like a meditation thing where I’m really out, I’m just really not thinking about stuff…

What kind of art do you produce?

So the thing is that my work that’s something that now that I’m starting to change again because I had some kind of a plan that I would cut off any kind of art just focus on this thing that I am doing and really keep doing it until it becomes like a technique then I’m really able to do it almost blindfolded. It’s just like as I see it for me my favourite colours are black and white, this is how I see colours more, I prefer colours this way anything that is black and white, even pictures I like it way much better. So I just kind of have the same patterns same kind of drawing but it’s always changing because I’m putting it into outlines.

Manaf starts showing us the artwork he’s produced and his room, itself a work of art.

…. So this is the first three posters that I started with, I already did them and that kind of put me out there in Berlin….

How do you describe that technique?

That’s the thing. So it’s not always something I’m instantly drawing, sometimes it’s just outlines of something. So here I took the outlines of Darth Vader and just drew Darth Vader you know…

so I started with this, like this is the big thing because Joans printed the really small drawings on notebooks and then we started there and now I am doing…

…this is my wall and I am doing really really big canvasses you know…

…so this is actually now what I, this is the only thing that I am projecting kind of, my exhibitions, my art, my whole thing…

That’s why I am not seeing myself so much as an artist especially in Berlin because artists here are all in all, he can really do it all, you know you can give him a sprayer and he gives you a graffiti that’s three metres, two metres big. So like now I’ve reached the level again where I’m really good with this black and white stuff and I want to start adding colours and some digital art.

Before we go let’s chat to Kien Quan, creator of ‘Made By Refugee’. The sticker and mural campaign started this March and it reminds us of the contributions refugees have made to our lives throughout history. It’s been well received.

It was just a simple little rant talking about how if this guy named David Tran didn’t come over from Vietnam as a refugee nobody here would be praising how much Sriracha is great over here and if you know much about what’s happening in the US right now, the biggest trend is Sriracha Hot Sauce. So it was really funny, you know there’s a lot of people who go against refugees and everything and I realized that and you know it’s really hard to argue that because they have contributed so much throughout history because refugees are humans they’re not useless people in society that drains on a city’s resources and I just wanted prove that. Everyone has potential and everyone has value and that’s the reason why I started this project.

Why stickers and murals?

I mean the idea was there to show that refugees have more potential than people really think in public and we’re trying to figure out what’s the best way to put out there and we’re in the advertising world we might as well use what we know to our advantage and push a good message out there because we could always be selling products but why don’t we sell an idea that really impacts the world. We just moved forward and decided stickers was the best way, its cost free and stickers, graffiti there’s always an air of political activism and I felt like that was the perfect way to get the message forward.

Can you give me an idea of the people you were trying to recognise?

I mean honestly I was just looking for a good angle I was looking for tangible products that people use and then it got a lot deeper, some of them were products you find on shelves. You know even Steve Jobs’ father was a Syrian refugee, there’s just so many things that go back to the idea words like ‘without them you’d wouldn’t be able to enjoy these things here’. You know things from this to cars, to philosophers to scientists, to physicists, to Nobel Peace Prize winners.

What’s next?

I feel like hype comes in waves, if you’re on that wave it’s good to ride it because that’s when you’ll get the most information out, but we’re definitely coming up with new ideas at the current moment and we’re working with another entity called Refugee nation. We’re at the drawing board trying a couple of new ideas to get this point across around the world because it’s a project but we really feel like this is a project, it’s something good, something that really comes out of our hearts that we really pour into.

Before you go, make sure to check out our gallery showcasing artworks from Manaf, Parmis and Poetry from Yousif.

In the next podcast we’re discussing the dangerous world of human trafficking along one of Africa’s most well known routes. We’ll be speaking to journalists, academics and organisations documenting the harsh reality, its financial connections and ways to monitor it on the ground.

Until then you can follow us on our social media. Check out our latest updates on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube and AudioBoom… or you can support our rescue missions by giving whatever you can to help us save lives at sea. Don’t forget to like, comment and subscribe for more podcasts from us.

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publ ication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

ication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.