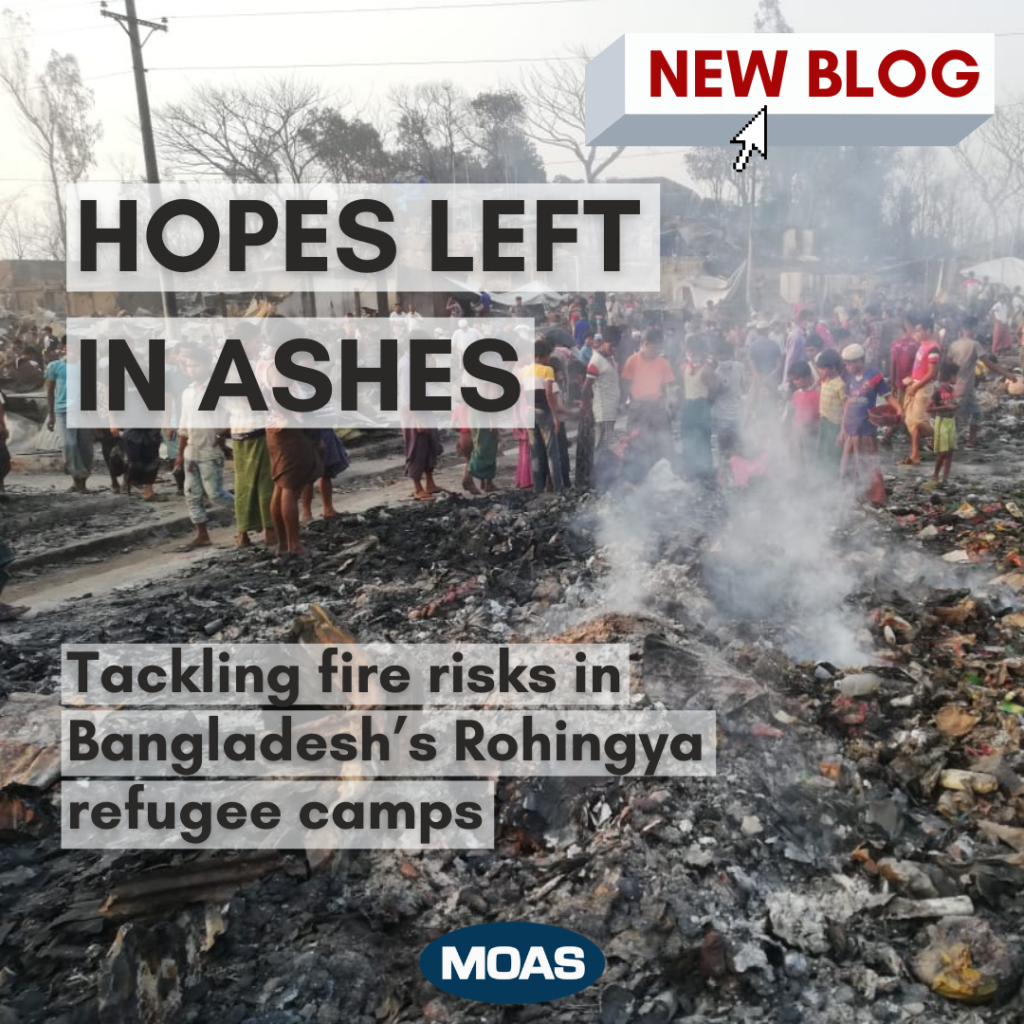

Fires are a persistent and terrifying threat to those living in camps for refugees and displaced people across the world. On March 22, a deadly fire broke out spreading across three connected refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. The blaze claimed several lives, with young children among those killed. An estimated 48,300 people lost their shelters and belongings.

The devastation extended across a town-sized area. Aid agencies are now scrambling to ensure the more than 10,000 families affected have sturdy shelters rebuilt by the time the monsoon arrives in May, amongst Covid-19 restrictions. But the losses of those whose loved ones perished cannot be repaired.

One father, 33-year-old Shahid, described the terrifying moments the blaze engulfed his shelter. He was inside with three of his four children when the fire started:

“I tried to dress my children and we ran out as soon as possible. The flames were very fast and in a few seconds they spread everywhere. There was also a lot of smoke.”

Shahid, described how his four-year-old son Kabir was out playing when the flames started and perished in the blaze.

“When we found him, his body was reduced to ashes. We have lost our son and all our possessions. Of what we had managed to scrape together in these four years [since fleeing Myanmar] all that remains is ashes.”

Fifty-year-old Mohammed was able to save his family during the March 22 fire but is among those who lost all his belongings.

“The fire engulfed our hut. The heat was unbearable, and the air thick with black smoke. Some of [my family] suffered minor injuries in the confusion of the escape, but luckily we are all fine,” he said.

“We have lost all our possessions, the few things that made up our world: clothes, food, dishes, beds, blankets. We do not know what caused the fire, it is difficult to say, but what we do know is that now we have nothing left. This fire has taken everything away from us, has reduced hope to ashes.”

Sadly, while the scale of the March fire was unprecedent in the camps, it was not an isolated episode. According the UN in Cox’s Bazar, a longer-than-usual dry season has exacerbated fire-risk in the area contributing to the 84 blazes that have broken out across the world’s largest refugee settlement in the first four months of this year alone.

In mid-January this year over 550 shelters were destroyed in one such fire. A few days later a second major blaze ripped through a nearby camp. The refugee community is now living in fear of further fires.

Cox’s Bazar is not an isolated case, and several other fire incidents have been reported in refugee camps worldwide. Readers in Europe will likely recall the miserable scenes from Greece last September when fires destroyed what was then Europe’s largest migrant camp, Moria, on the island of Lesbos. The flames left nearly 13,000 people without shelter. As people, many suffering from smoke exposure, fled the burning camp, police blocked roads to prevent migrants entering nearby towns.

Refugees and IDP camps – which are in reality makeshift towns, even cities, in terms of number of inhabitants – are generally desperately over-crowded, haphazardly erected and constructed of highly flammable materials.

Many, such as the camps in Cox’s Bazar, have sprung up in the midst of massive humanitarian emergencies. When hundreds of thousands of people flee over a border in just a few weeks – as happened during the 2017 Rohingya crisis – providing the most basic necessities of water, food and protection from the elements are massive organisational challenges in themselves.

There is little room for forward planning such as fire-risk assessments during that initial rush to save lives. In Cox’s Bazar many shelters were erected by refugees wherever they could find space and extremely close together. Unfortunately, the legacy of such initial emergency response actions by people in need and those attempting to assist them can be hard to unpick. As a consequence, many of those facing protracted displacement such as the Rohingya – most of whom are treated as stateless by their home-country Myanmar – can spend years living in accommodation and surroundings that are extremely vulnerable to fire with limited access to fire-fighting resources.

The internationally Sphere Handbook on humanitarian standards, notes in its shelter and settlement standard 1 that shelter interventions should be “well planned and contribute to the safety and well-being of affected people and promote recover”.

However according to logistic experts there are “no guidelines published in Sphere for fire-fighting. There are for fire breaks but, given the cramped and unplanned nature of many of the camps in Cox’s Bazar, they have not been followed in the main.”

A study by IOM into fire-risk in the camps identified open-fire cooking, as widely practiced by Rohingya families in Myanmar and after arriving in Bangladesh, as the one of the possible main cause of uncontrolled blazes.

A number of UN agencies and other organisations have worked to mitigate fire risks for refugees and residents in the host community including through: Provision of LPG gas stoves to reduce use of open fire cooking; providing training in firefighting to volunteers in the refugee and local communities; and creating fire points with sand buckets for fire extinguishing. Newer shelters have also been built in a more planned way. Nevertheless, the risks remain grave, particularly in the older, most crowded parts of the camps. While LPG stove use is considered notably less hazardous than open-fire cooking, the canisters themselves can pose a risk of explosion if not used or stored safely.

Among the recommendations of the IOM report into fire risks, longer term improvements include: more water sources with pumps and hoses available to trained firefighting volunteer units; additional training, particularly leadership training, for volunteers; and improved evacuation plans.

If you are interested in the work of MOAS and our partners, please follow us on social media, sign up to our newsletter and share our content. You can also reach out to us any time via [email protected]. If you want to support our operations, please give what you can at www.moas.eu/donate.