Every year, Refugee Week provides the opportunity to come together to celebrate the creativity, contributions and resilience of people experiencing forced displacement, particularly through art and poetry. Today, we share the work of three poets examining what it means to be a refugee and the experience of exile. If you would like to share your own poem on the theme of displacement with us, please email us at [email protected].

Eric Ngalle Charles is a poet, author, playwright and Cameroonian refugee now living in Ely, Wales. Eric has written extensively on the theme of seeking refuge, and now works with refugees and asylum seekers to help them make sense of their experiences of forced migration through the process of creative writing.

When Exile Comes: (How the Brain Reacts to Trauma)

That day, I prayed in a tongue

I did not understand,

In a language, I did not speak.

I laugh.

Rain bouncing on my back,

My wrinkles hiding the passage of time,

Living as a stranger amongst my own.

I cry.

I do not remember my dreams,

the sun rays avoid my skin.

My shoes have holes.

I paid my debts a thousand times

to those who planned to kill me.

I laugh.

This is my grave,

This is my grave

I stand in a field of Daffodil

I am Waiting for you,

I am Waiting for you to bury me.

Jay Kjapra is an aspiring entrepreneur hoping to make the world a better place. He will occasionally let his creative juices flow through poetry.

Doomsday Harvest

Bare to the bone

Cracked and withered lands

leading to broken fortunes and tortured souls,

a raging war casts a dark shadow

Let the reckoning wait

Buried seeds bring new hope

of promise to a dying breed

The past brings new future

for a golden hue to rise again

Let the reckoning wait

Yousif M. Qasmiyeh is a Palestinian poet, translator and Arabic tutor at Oxford University. He was born and brought up in Baddawi refugee camp in Northern Lebanon. He is the Writer in Residence with the Refugee Hosts project.

In mourning the refugee, we mourn God’s intention in the absolute

How can there be a camp apropos a world?

We repeat the repeated so we can see our features more clearly, the face as it is, the cracks in their transcendental rawness and for once we might consent to what we will never see.

They rarely return – those pigeons. The piece of wood that was meant to scare off the pigeons and entice them to return to their home landed by my feet. Not knowing what to do with it, I shut my eyes and threw it back in the direction of God…

Shadow, leave your body alone.

In cremating the shadow, we cremate time.

The name is the loneliest of things.

In what we cook we trace the hand. We glimpse its dried blood with every mouthful.

The refugee promises within his own means.

The camp, the allegorical of the allegorical.

What is recited is the voice and not the text.

In my camp, women slap themselves in funerals to never let go of pain.

Solitude, the spirit at home.

Who can see it to say: it is? Who has the eyes to say: it definitely is?

The pious are banging on the door. The pious have arrived to recite the name, a name like any other…

The camp in as much as it repeats time never acknowledges it as a divine authority.

The eternal in the camp is the crack. “The crack also invites.”

What is a camp? Is it not a happening beyond time?

A camp, to survive its happening, must become almost a camp.

It is what the hands contain at a juncture of their own making, never salient enough to be spotted by a passerby or a departing face. Nor is it close enough to be grasped by random fruit pickers humming bygone songs.

A life awaiting to grow behind itself.

A life on the edge of the edge.

The sublime in the camp, what it is? Can it not be the camp gestating with its impossible meaning?

His feet were in water and the hands were by his side as flat as nothing. While the tea was brewing, he prodded his father’s shoulder to ask about the number of graves he dug today.

In overthinking the position of the dead when all eyes are transfixed on the hole we bury time in the past.

Nothing can outlive Nothing when Nothing escapes not the idea of living, living like twigs left alone to decay under the sight of the mother tree.

Does the camp not have a gender?

What speaks in the camp is nothing but the foreskin.

Arise from water with the barest minimum of a thing like someone whose completeness is incomplete except in the bodies of God.

No shadow for water. They walk, as though they were hand in hand or towards each other’s feet, no one precisely knows where the cracks are taking them.

These are not headscarves but heads forever wrapped in themselves.

In mourning the refugee, we mourn God’s intention in the absolute.

A ponderous death. Bodies float above water. Clarity happens. Nothing or its birth?

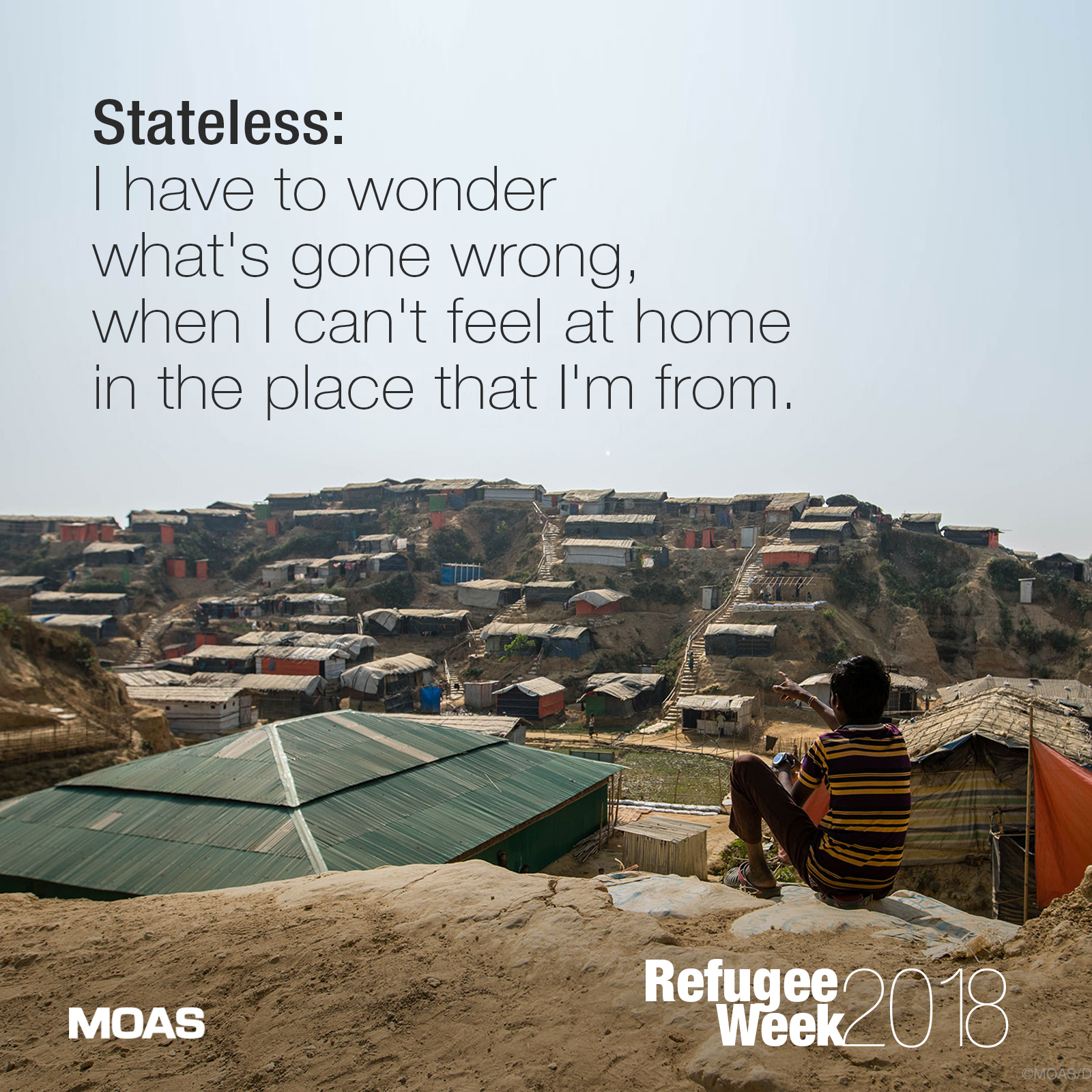

Make sure to stay tuned throughout Refugee Week and share your own #SimpleActs of solidarity on social media. You can support our work in Bangladesh by donating here, or fundraise with friends to become a part of our activist community. You can also receive regular updates by signing up to our newsletter at the bottom of this page or following us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.