Content Warning: Some of the descriptions from the beginning of this podcast/blog may be upsetting for some listeners.

Content Warning: Some of the descriptions from the beginning of this podcast/blog may be upsetting for some listeners.

When we think about Opera, we imagine stories of mythical gods or tragic love stories. They’re also about topics that challenge us. This is one of them.

AĦNA REFUĠJATI or ‘We Refugees’, is the first of its kind in Malta.

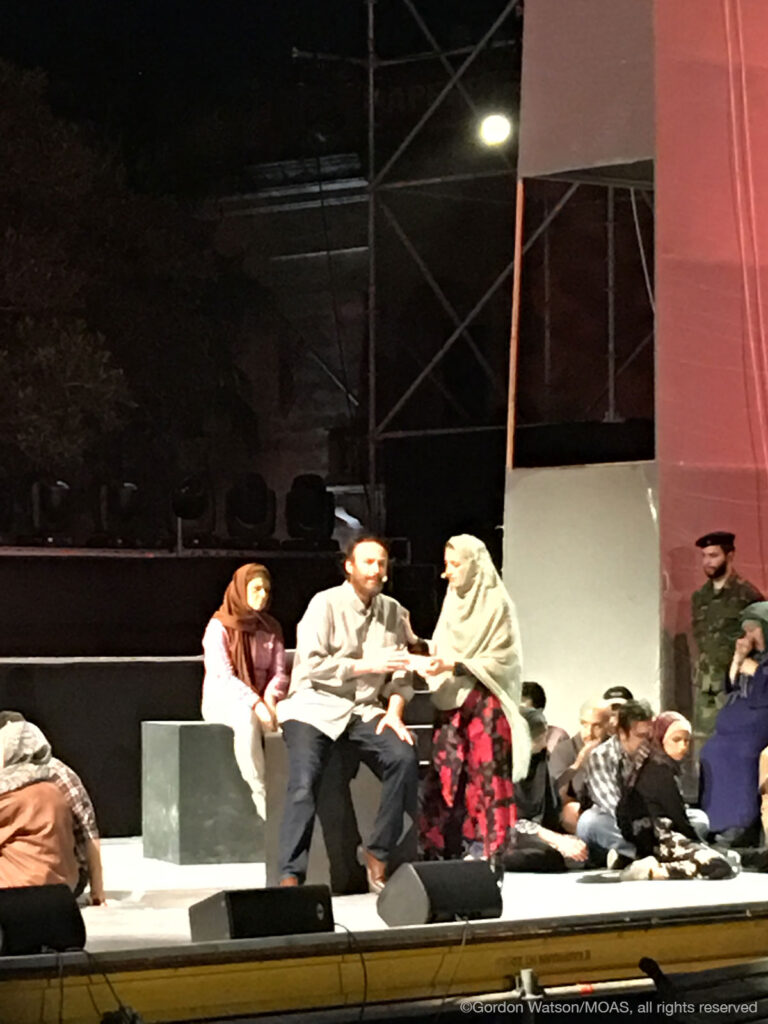

With the current migration crisis as its backdrop, it follows a family’s physical and emotional journey fleeing war, in search of safety in Europe. Right from the opening scene, audiences are thrust into their story.

‘In the first five minutes of the opera, we have four beheadings of another family. This father realizes that if they stay there, they will end up the same, their heads are going to end up on poles. They’ve got to leave. We see two executions in the first five minutes and four beheadings. How’s that for an overture. They leave and they have to go through hell in order to go towards Europe.’

That’s the Opera’s Artistic Director, Mario Philip Azzopardi.

After a long career in TV and Film, Azzopardi wanted to write an opera, one that exploits its visual and musical impact but also tell a relevant story of our modern times; refugees and migration.

It’s a problem, one he wants Europeans to stop running from and work towards solving.

‘we’re going to do something that talks to us as a society, use the opera not only as an artistic medium but as a medium that helps us understand ourselves. Like for example in ‘Il barbiere di Siviglia’, you have a story where you have a girl that is afraid of telling her father that she has a boyfriend, how does that relate to today’s society?, who cares?. It’s something to be given back to the people, and we’re going to give it back to the people, we’re going to talk about something that they know about.’

The opera performed all in Maltese, brings together a cast of well-known local and international talent, this time singing without a live orchestra. Miriam Gauci is one of them.

She plays Shari, wife to Eleja and mother to her three children Hamid, Saja and Darit. At first, she was hesitant about the role but she says that Malta’s own migration history carries strong parallels with the current situation.

What I thought about in myself was that even if you look at the Maltese history, after the war, thousands of Maltese had to leave the island to start life elsewhere. So, it’s not really refugees, its immigrants but still, one has to deal with another lifestyle, it’s not your country. All of these situations, this situation in this opera, they belong to real life, so it can be what’s happening now elsewhere in the world so it’s something that one should think about. I have to speak for myself as Catholics, I mean, don’t put any religion in this but I think that we should help everyone, anyone. It has to be that way.

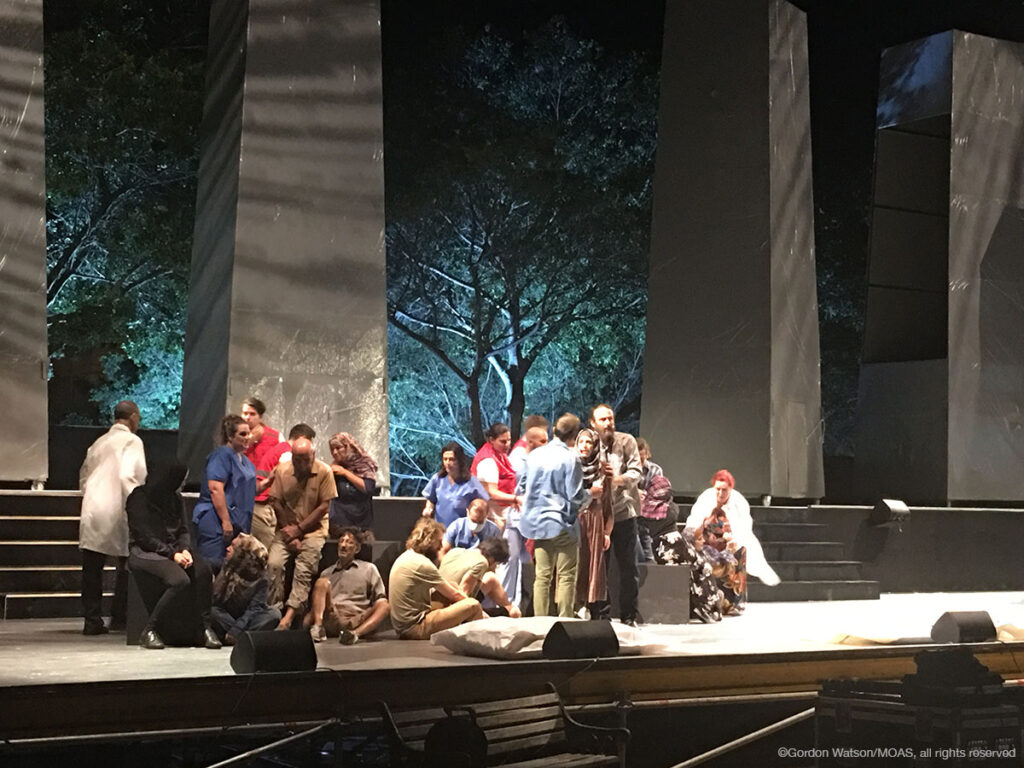

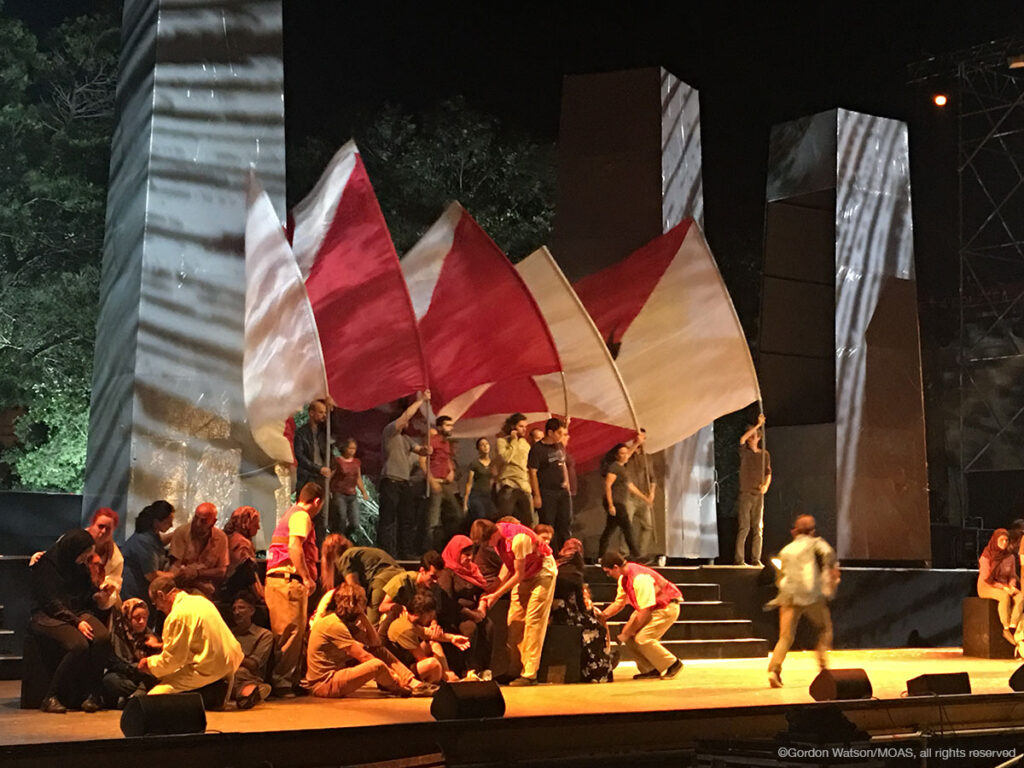

Just outside of Valletta is Il Fosos, Malta’s old granary stores and the temporary home to the open-air Opera. It’s a production that’s taken three years to make, from the writing of the story to the mammoth task of recording and arranging the music.

On the stage are stood eight obelisk structures, all painted a cold grey. They’re an imposing plot device, changing scenes and showing the closure and breaking down of physical and abstract borders.

Ever since the first deaths of migrants crossing the Mediterranean reached public attention, Malta has been directly involved. And, with recent political changes in Italy and Europe, the island nation has become a ground zero for debating who should accept rescued migrants. For the cast, performing has helped them get closer to a crisis they’d only seen on TV.

‘You know the statistics but when you are on your sofa watching TV, sometimes you wonder how they feel. You are not able to have empathy, I have to confess that. But with this Opera I had the opportunity because Mario Azzopardi, he wrote, in my opinion, such a good libretto where you can smell the situation. You are on the boat and you hear little Darit, my little daughter sing, ‘I’m scared, I like the sea when its blue but I don’t like it when its black’, because it’s in the night and its dark, she’s afraid. You know, you have the time to feel, it’s an opportunity to have empathy and I think that’s a good thing for the audience and myself.’

That’s Spanish counter-tenor, José Hernandez Pastor.

Playing the husband and father, Eleja, carries the weight and shift of the opera’s emotions on his shoulders. From fear and guilt to depression, Eleja tries to find a glimmer of hope to live for his surviving children.

‘there is a moment, we are on the beach still, being attended by the volunteers, the locals are shouting, ‘barra’ ‘barra’ ‘go out’ ‘go out’ and I am asking for my wife and my daughter because I still haven’t found them and I don’t know if they are alive or not. There are people who are separated from their families and they are hearing ‘get out’’

The opera has been generating attention and ever since the production was announced back in July, social media in Malta had ignited with comments both praising and condemning it.

For Joseph Zammit, who plays Hamid, critical comments show that the opera is doing its job to open up the debate in Malta.

‘When I read those comments, I laughed to be honest because they’re words hold no value. They were saying that this Opera is ridiculous and horrible without ever hearing what the story is about to begin with. So, they are comments to be ignored. But, I guess on the bright side, some attention is garnered for the production, not to say that there is no such thing as bad press but it’s helping put up the point for this Opera being made.’

AĦNA REFUĠJATI is indeed a new type of opera and it wants to make the audience think and talk about a modern issue, using opera to deliver its message.

Its story is timeless. Here’s Nico Darmanin,

‘this story it’s very different, its very relevant to nowadays stories, but it is in essence a story about love, tragedy, death, a fight for freedom which I think is the most in my opinion the most important fundamental human right. So yes the story is very relevant for today and basically we’re giving an entertaining story for the public that is something they can relate to rather than something that happened 300 years ago.’

The wait is finally over. The house lights illuminate Il Fosos as people enter and take their seats. Backstage, the final checks are being made, the cast micced up and the obelisk movers in position. Nervous excitement rests among those backstage, as the crew call their final commands before curtain up. Standing off stage, I recall Jose’s feelings ahead of tonight…

‘It’s like you’re asking me, how much will they listen? It’s how able are we, how prepared are we to have empathy even if we know that statistically the solution is not just taking them, that is not the whole solution but you can’t leave them on the sea, you know? of course, this will be like a bell and it’s like everything, maybe on the first bell they wake up, or maybe we wake up or you need 20 bells. This is a good one, this is a good bell to sound in my opinion.’

If you liked this Podcast don’t forget to hit like, comment and subscribe for more Podcasts from us.

You can also follow us on our social media. Check out our latest updates on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube and AudioBoom… or you can donate to help us help Rohingya refugees .

From all of us here at MOAS: goodbye.